Carefully-considered memoir about race, belonging and growing up in Australia

I received a copy of this book courtesy of the publisher, however I have been looking forward to it for a long time ever since I found out the editor of Feminartsy (a journal I write for occasionally) was working on it. I also interviewed her in the most recent episode of my book podcast Lost the Plot.

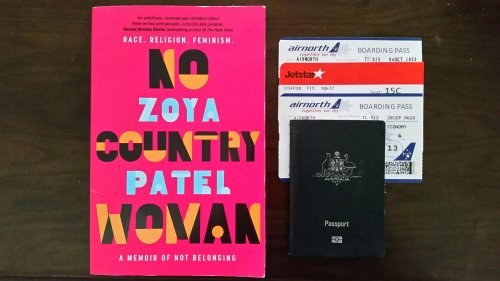

“No Country Woman” by Zoya Patel is a memoir about growing up as a third culture kid with a Fijian-Indian background in Australia. Divided into loose thematic chapters, Patel blends personal experience and social theory to reflect on what it means to belong somewhere and the colonial and economic drivers behind generational migration.

This book is an excellent insight into what it is like to navigate two cultures. Patel has a crisp, cool writing style and patiently and piercingly walks the reader through issues such as racism, poverty and identity. She unpacks the theme of belonging in exacting detail and examines what it means to look the same, sound the same, share the same cultural identity and share the same beliefs as people in Fiji, Australia, India and Scotland.

I particularly enjoyed Patel’s words on economic inequality, and her chapter on poverty in India. I think that examination of class is often absent in other memoirs I’ve written, however Patel is forced to confront issues of privilege on a family visit to India as a child and the stark comparison between the lives of family who left and family who stayed. I was also really fascinated by Patel’s experience with language, and the complexities around language, identity and belonging. In a country where the number of people learning a second language in school is on the decline, I was interested to read about the role of language in belonging and the interrelationship with cultural identity.

I think it needs to be said that this is not a book about overcoming adversity in the same way as other women of colour like Maxine Beneba Clarke‘s horrendous high school bullying experience and Roxane Gay‘s trauma as a teenage girl. It certainly isn’t filled with the same rage and hyperbole as Clementine Ford‘s book either. Patel’s family are tight-knit, resilient and entrepreneurial, and are the backdrop rather than the focus of the book. While this book is certainly very personal in many parts, Patel has a measure of reserve that sets this book apart from other memoirs.

While sometimes it can be incredibly engaging to read something that seems entirely unfiltered, I think that Patel’s memoir serves a different purpose. Rather than being an exposé of self, it is an exposé of systems, and provides an academic lens through which to examine personal experiences. While some people connect with the ultra-personal, I think that this style of memoir is particularly effective and I think most readers would find it hard to argue with or minimise Patel’s points.

Memoir is a growing genre in Australia and is an excellent way to explore different perspectives. This book is a particularly sharp look at the realities of race and migration in Australia, but more importantly the diversity of those experiences.

This sounds excellent and like it hits on some very important topics. Fantastic review!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! Looking forward to your review!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

This sounds really interesting and I’m looking forward to reading it, especially after your comments and observations. Issues of inequality always interest me, especially in a country like Australia which likes to think it is class-less when it most definitely is not. Thanks again, Karen

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Karen, definitely agree that people don’t acknowledge issues of class enough at all

LikeLike

My, Angharad, your reviews are coming thick and fast at present. I’ve heard Zoya Patel talk and enjoyed hearing her perspective. I like your comment that this is more an expose of systems. Sometimes the personal can become repetitive. Looking at the issue from a broader perspective would be helpful I think.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Sue, I’m have a backlog of about 10 reviews after travel and work haha so had a bit of time this weekend to try to catch up. Agreed though re: the personal, this book is almost more like a collection of essays

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well, well done you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Only | Tinted Edges