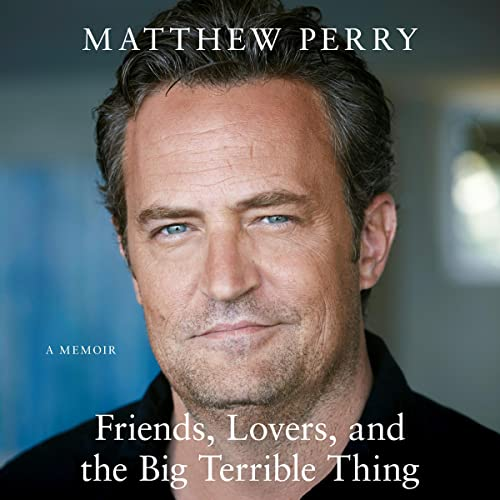

Celebrity autobiography about TV fame, drug addiction and mental health

There have been a lot of celebrity biographies coming out recently, and I’ve listened to Jennette McCurdy‘s and Prince Harry‘s as audiobooks. When I saw that this one had been published, I was pretty interested. Just about everyone has watched the TV show “Friends” (enjoy the now retro Blu-ray trailer!), and the character Chandler was one of the most iconic of the series. When actor Matthew Perry died recently, almost a year after it was published, and it came up on my recommended list, I picked it as my next audiobook.

“Friends, Lovers and the Big Terrible Thing” written and narrated by Matthew Perry is a frank memoir about his life and how he came to be one of the most famous actors on one of the most watched television shows of all time: “Friends”. Perry writes candidly about his experiences growing up in Canada, the child of two charismatic parents whose marriage ended, and his early forays into acting, alcohol and drug abuse. Perry charts his path to winning the role of Chandler on “Friends”, and how despite his immense professional success, he nevertheless continued to struggle with addiction and mental health issues.

I think one of the best things about this memoir that makes it stand out from others is that despite Perry’s fame, it isn’t ghostwritten. Perry has a humorous, self-deprecating way of writing and pulls the reader in with intimate revelations about himself and his life. One thing that has frequently frustrated me with the memoir genre is authors sharing either not enough or far too much, and I felt like Perry really struck the right balance. As challenging as he clearly was as a person (to others but mostly to himself), self-sabotaging constantly and pushing people away even when he was at his most lonely, he makes the reader feel like a confidante. I enjoyed his narration a lot, though I did find it less clear and articulate than his delivery of lines while he was on TV. I was impressed that despite his own frequent relapses, he nevertheless strove to inspire hope to other people struggling with addiction.

It was a bit of a strange experience listening to this book shortly after the news broke that Matthew Perry had died. It really made me read into what he wrote a lot more. While Perry doesn’t claim to have the answers to addiction, the end of the book certainly suggests he is on an up, and suggests that his own brand of spirituality has helped him. However, I think this book really underlines the message that addiction is a disease, often a lifelong one, and there is no easy cure. Perry wrote a lot about his parents, colleagues and former girlfriends, many of whom witnessed his struggles firsthand, and I did find myself wondering how honest those reflections were. Some seemed a bit rose tinted, some seemed a bit unfair and I found myself wondering how the celebrities mentioned would have received it. I think it’s difficult to criticise something so subjective as what causes a person pain and trauma, but as a reader it is a bit hard to accept things that seem relatively minor when that person enjoys enormous success and wealth and has access to the most expensive and cutting edge treatment available. Perry does come across as one of those people who spends an enormous amount of time self-reflecting, but who never seems to gain any real insight into their behaviours and motivations.

A forthright memoir about privilege, success and struggling with mental health.