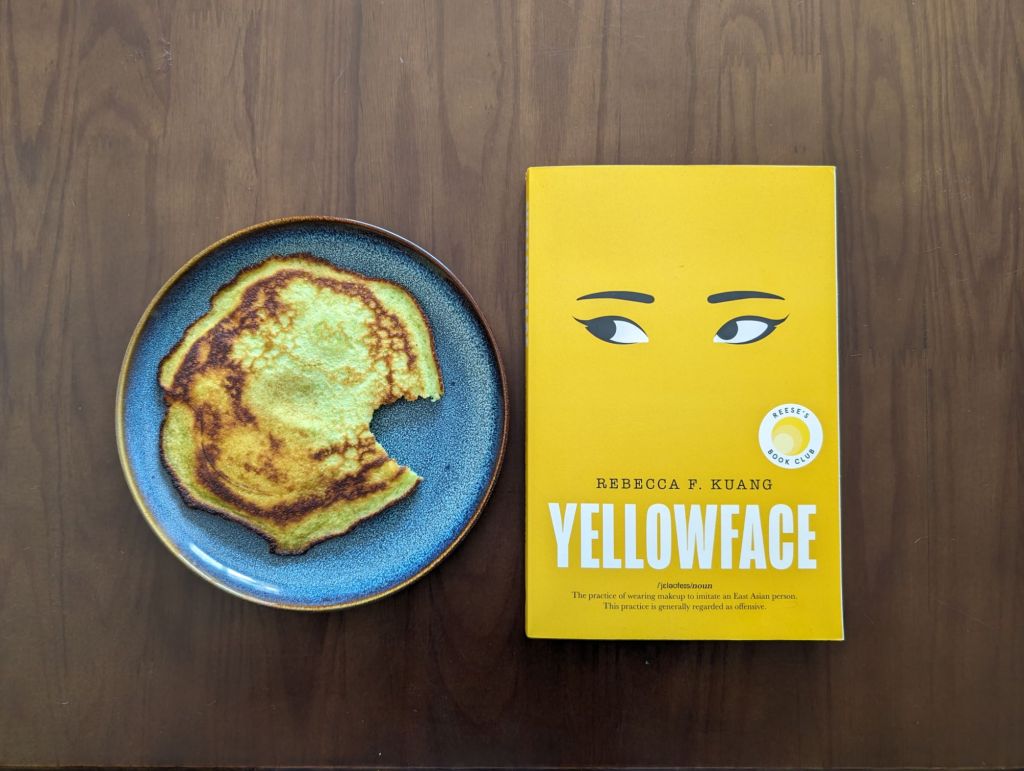

Satirical novel about jealousy, plagiarism and Own Voices in the publishing industry

I know this author from her fantasy series which I first read some years back. She has recently made a stir in the book world with her foray into literary fiction, and I picked this book as my next gardening audiobook to read. By sheer coincidence, my sister bought me a paperback edition for Christmas thinking it would be the kind of thing I would like. She was correct, and it meant that I was able to take a photo rather than just share the audiobook cover.

“Yellowface” by Rebecca F. Kuang and narrated by Helen Laser is a satirical novel about a young white writer called June who is friends with Athena, a vastly more successful Asian-American writer. Although their friendship doesn’t appear much closer than acquaintance, after a night out together results in a fatal freak accident, June finds herself in possession of Athena’s next project. What follows is a morally fraught chain of events where June’s newfound success draws more and more criticism.

This is a clever and biting novel that tackles issues of cultural appropriation, plagiarism and how trials by public opinion play out through social media. The story is told in first person from June’s perspective and she is a delightful villain whose capacity for self-delusion is truly remarkable. June’s ambition combined with a lack of any special talent or originality set her up to seize an opportunity that most (but not all) writers would never consider taking. Kuang explores the conversations around these issues smoothly and as a reader, you find yourself filled with both schadenfreude and begrudging empathy as June’s actions snowball. Exactly how this plays out is supported with excerpts from emails and Twitter threads. I particularly enjoyed Kuang’s explorations of the common idea that someone’s success in the literary scene may be because of their ethnicity, rather than despite it. I also really liked how Kuang provided a behind-the-curtain understanding of how things work once you have an agent, a manuscript and a publisher and how much (and how little) authors are supported to sell their work.

A keenly insightful and thoroughly enjoyable book.